There is a problematic disjunction in dementia research: by 2050, it is estimated that most people living with dementia will reside in countries where there is lower economic development (Alzheimer Disease International (ADI), 2015). However, much of the research undertaken in dementia takes place in high-income countries.

So why is this a problem?

It can be a problem because of how we conduct our research. Psychology has long been criticised as ‘WEIRD’, with an overriding focus on Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich and Democratic nations (Henrich et al., 2010). Resulting theories and interventions are, by necessity sometimes, culturally specific. Dementia, however, is not culturally specific. We need to adopt a global approach to our research and care to ensure that people with dementia, no matter where they live, can access meaningful, culturally appropriate, and evidence-based interventions. Do we then adapt our approaches or innovate and develop new approaches? Currently, we largely adapt and there are benefits to doing so. However, here I present a case for the benefits of innovation over adaptation.

An example of innovation in action comes from Positive Psychology theory. Positive Psychology approaches are increasingly applied to people with dementia in Western countries. This study of positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning and accomplishment (Seligman, 2018) is important for understanding wellbeing and has been long overlooked for people living with dementia. Older adults with dementia, like anyone else, experience many positive aspects of life, but, until relatively recently, our research in psychology told a very different story. We focused on loss, decline and dependency almost exclusively. This progress in understanding the strengths and capabilities of people with dementia can give us fundamental insights into wellbeing. However, Positive Psychology is a Western theory, with particular criticism levelled at its focus on the self as being less relevant for those residing in other cultures (Christopher & Hickinbottom, 2008).

How then do we ensure that progress made by researching the strengths and capabilities of people with dementia continues in a meaningful way across countries despite the inherent issues with the Western theory? A first and often overlooked first step in the innovation process can be a theoretical paper exploring concepts across countries and cultures. Going back to our Positive Psychology example, a recent paper proposed a framework for how we might understand positive psychology in the Chinese context (Lau et al., 2021). In this paper, we see how traditional positive psychology concepts like social engagement and wisdom, are better understood in the Chinese context as interpersonal and intrapersonal harmony. These concepts were developed from and are rooted in traditional Chinese values of filial piety (in which individuals are taught from a young age that elders should be respected and obeyed) and reasoning. This suggests an important difference: East Asian populations may have a greater emphasis on oneself in relation to others as opposed to oneself in isolation. This resulted in an innovation: a new Positive Psychology framework for older adults with dementia in China, focusing on those interpersonal relationships.

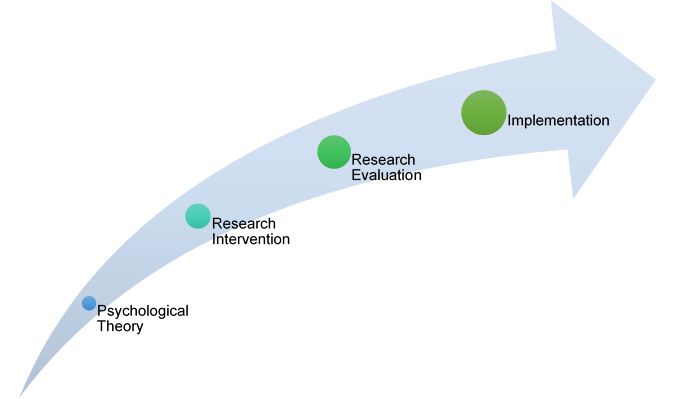

Moving beyond theory, we think about practical applications of psychology. Let’s take the example of a psychological or psychosocial intervention for people living with dementia (Moniz-Cook et al., 2011). Often, researchers and academics will go to great lengths to develop meaningful interventions for people living with dementia. This can include detailed examinations of the research literature, consultations with the public and a research evaluation. This is gold-standard intervention development, and recent striving for patient and public involvement in research in particular has been fundamental in developing interventions that people with dementia really value. However, if you consult with and develop an intervention with, for example, older adults living with dementia in the United Kingdom (UK), by necessity, your intervention will have some cultural specificity.

Culturally specific interventions mean that anyone else wishing to use these interventions has to adapt the intervention to their setting, but it’s not always clear how this is done or indeed the best way of doing this (Stoner et al., 2019). There have been recent efforts to adapt psychological interventions using large scale global partnerships. One such partnership between academics in the UK, Brazil, India and Tanzania to adapt Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (CST) for people with dementia in these countries has highlighted just how complex this can be. Barriers including variable costs, reliable access to care and availability of staff are just three of the many considerations one must take when using a psychological therapy designed for use in another country. However, innovation was key to ensuring this intervention was meaningfully used, with ‘Implementation Plans’ developed by the partnership for each city, in each country, to explore how best to translate CST into care or practice for older adults with dementia in that specific context (Stoner et al., 2020). This innovation resulted in a tailored approach to the use of this therapy across countries, improving access to a well-evidenced therapy.

Once we have a theory, and an application of that theory, a research evaluation is needed to test if it is indeed beneficial to people living with dementia. We currently have a plethora of tools to measure the relative success of psychological interventions in dementia research. However, these tools can follow the same pattern as theory and application: they are developed in the West and adapted for use elsewhere. Sometimes, it is not always clear the degree to which these tools have been tested prior to that research intervention to ensure that terms and concepts remain similar across countries (Du et al., 2021). In the context of the Positive Psychology example we again see why it might be problematic to assume the measurement of a concept is similar across countries.

How do we move beyond this? There is no simple answer here and the above are simplistic explanations or interpretations of often complex areas of policy and research. The question is: is it possible to shift away from adaptation, recognising the inherent difficulties at the theory, research intervention and evaluation stage in psychology? At the moment, we are driven by adaptation, with small pockets of innovation. Where innovation occurs amongst the adaptation, as in the examples given here, we can see how beneficial these small pockets of innovation are. Perhaps then we can use this as a springboard and develop more of these global partnerships to slowly shift our focus toward innovation with small pockets of adaptation. Such partnerships may hold the key to developing equitable, culturally appropriate, meaningful dementia research across the world.

Whether this is possible or not, recognising that these problems exist and considering psychological theory, interventions and evaluations through a global lens can only improve the lives of people with dementia, which is what we as dementia researchers all strive for.

Dr Charlotte R. Stoner is a Lecturer in Psychology at the University of Greenwich. Her research interests include the development of strengths-based outcome measures for older adults living with dementia and global health approaches to dementia. Examples of measures developed include the Engagement and Independence in Dementia Questionnaire (EID-Q) and the Positive Psychology Outcome Measure (PPOM).

References

– Alzheimer Disease International (ADI). (2015). World Alzheimer Report 2015, The Global Impact of Dementia: An analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends (p. 87). Alzheimer Disease International. https://www.alzint.org/u/WorldAlzheimerReport2015.pdf

– Christopher, J. C., & Hickinbottom, S. (2008). Positive Psychology, ethnocentrism, and the disguised ideology of individualism. Theory & Psychology, 18(5), 563–589. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354308093396

– Du, B., Lakshminarayanan, M., Krishna, M., Vaitheswaran, S., Chandra, M., Sivaraman, S. K., Goswami, S. P., Rangaswamy, T., Spector, A., & Stoner, C. R. (2021). Psychometric properties of outcome measures in non-pharmacological interventions of persons with dementia in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Psychogeriatrics, 21(2), 220–238. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyg.12647

– Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2–3), 61–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X0999152X

– Lau, W. Y. T., Stoner, C., Wong, G. H.-Y., & Spector, A. (2021). New horizons in understanding the experience of Chinese people living with dementia: A positive psychology approach. Age and Ageing, afab097. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afab097

– Moniz-Cook, E., Vernooij-Dassen, M., Woods, B., Orrell, M., & Network, I. (2011). Psychosocial interventions in dementia care research: The INTERDEM manifesto. Aging & Mental Health, 15(3), 283–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2010.543665

– Seligman, M. (2018). PERMA and the building blocks of well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 13(4), 333–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2018.1437466

– Stoner, C. R., Chandra, M., Bertrand, E., Du, B., Durgante, H., Klaptocz, J., Krishna, M., Lakshminarayanan, M., Mkenda, S., Mograbi, D. C., Orrell, M., Paddick, S.-M., Vaitheswaran, S., & Spector, A. (2020). A new approach for developing “Implementation Plans” for Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (CST) in low and middle-income countries: Results from the CST-International Study. Frontiers in Public Health, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00342

– Stoner, C. R., Lakshminarayanan, M., Durgante, H., & Spector, A. (2019). Psychosocial interventions for dementia in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs): A systematic review of effectiveness and implementation readiness. Aging & Mental Health, 25(3), 408–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2019.1695742